Why DAOs are the new firms

Polymarket - Bet on your Beliefs & Harness the Power of Free Markets

Polymarket - Bet on your Beliefs & Harness the Power of Free Markets

Zerion is Mission Control for Web3. Manage your portfolio, trade tokens, and display NFTs!

Dear Bankless Nation,

Last year DAOs hit an inflection point. Membership, treasury, and activity exploded.

To many of the young entrepreneurs and crypto enthusiasts, DAOs may seem like a radical shift in organizational power structures.

No boss? Getting paid in native tokens? Voting on decisions?

Could this actually work?

But each cultural phenomenon has a historical backdrop that should be well understood.

DAOs are not the first type of organization to tackle decentralized governance. In fact, many corporations are far more “decentralized” than we give them credit for.

Today, Donovan brings us this context by going deep on the history of the corporate firm and why DAOs are the natural progression of a decades-long trend.

- RSA

One of crypto’s lesser-known innovations (but much discussed on Bankless) is the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), a form of social organization built on blockchains and smart contracts.

Celebrity investor Mark Cuban heralded DAOs as a “combination of capitalism and progressivism”. In crypto quarters, DAOs have been called alleged as the “most important innovation” and the “future of work”.

DAOs, at their essence, enable people on a mass scale to coordinate, invest and work with economic certainty, thanks to the immutable and open-source nature of blockchains.

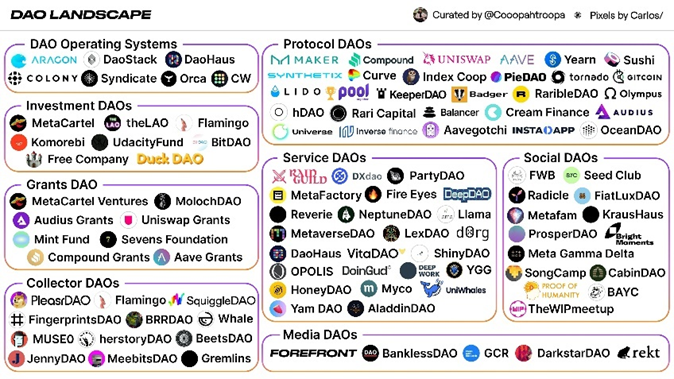

As of March 2022, about 215 DAOs are listed on DeepDAO handling $9.5 billion across half a million active members. DAOs come in a variety of categories across DeFi, fundraising/investment, social communities, media, service (freelance), and more.

Today I want to position DAOs within the historical development of the modern capitalist firm to better appreciate what these new social organizations are capable of on a logistical and economic scale.

The Nature of the Firm

We start with the most fundamental question: Why do firms exist at all? Why are markets an archipelago of large corporations and mid to small-sized firms instead of billions of freelance, independent workers and hirers?

The economist Ronald Coase poignantly argued that firms exist for reasons of efficiency. Firms are a mode of organization that helps capitalists reduce the transaction costs of doing business i.e., using the market. If CEOs had to haggle over the terms and conditions for every task with a worker, they would spend all their time mired in bargaining and micromanagement instead of entrepreneurship. The efficient solution was to set up a hierarchical corporate structure and engage workers in long-term contracts within them so they could spend time on managerial duties.

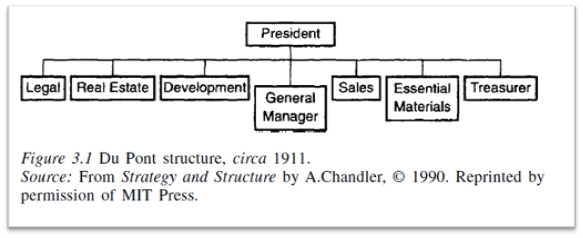

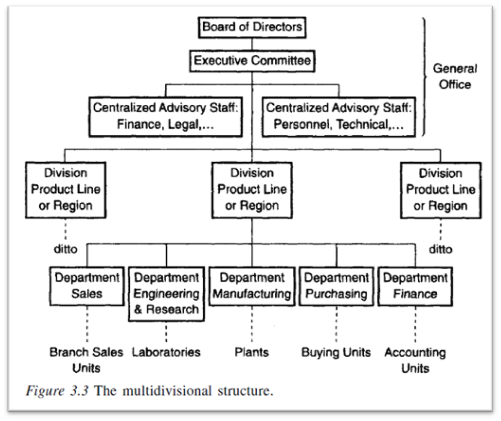

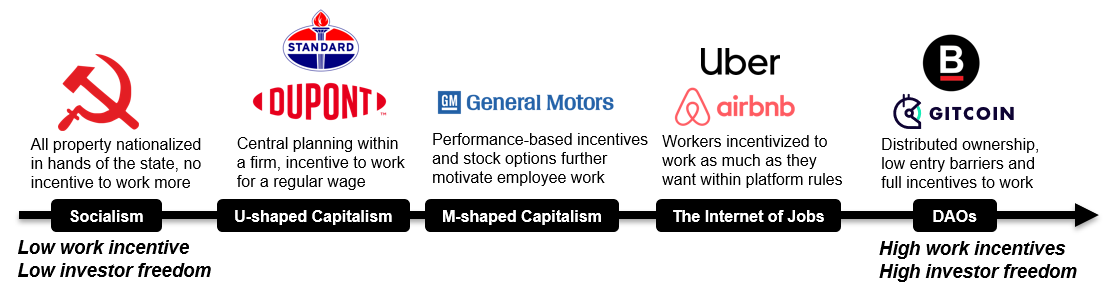

Coase developed his theory of the firm from an inductive observation of large, centralized corporation structures such as General Motors, Standard Oil, and du Pont in the late 19th century to 1950s. These large corporations were set up in a U-shaped (unitary form) structure that came to be synonymous with modern industrial capitalism and the most common organizational structure for decades, even until today.

This seems like an awfully commonsensical insight today. Yet, it’s hard to state how ground-breaking the Coasean explanation was in its time. Before Coase, economists treated the firm as a static black box that merely existed in the market economy. Post-Coase, the analytical thinking of the firm evolved into a complex management structure that juggled transaction costs.

Innovation of the U-shaped to M-shaped firm

The Coasean theory of the firm was not without its critiques. On theoretical grounds, it is unrealistic to suggest that one central planner at the top of a giant corporation could possibly oversee every aspect of the firm and instantaneously decide for every task whether to hire another employee internally or to outsource it on the market.

The Coasean explanation was steeped in neoclassical economic thinking where firm owners were assumed to be operating as rational calculators (homo economicus) responding strictly to market incentives and performing lightning-fast cost-benefit analyses.

By the 20th century, Coase’s theory of the firm was also getting overturned by real-world experience. As globalization increasingly interconnected the world’s economies, corporations pursued increasingly complex enterprises by diversifying into markets far from home.

The centralized U-shaped structure grew to be inadequate to manage an ever-increasing scope of complex administrative decisions. The weakness of the traditional U-shaped firm stemmed from its concentration of decision-making power in the hands of a few top men, making it too slow and cumbersome to adapt as the firm grew. Managing the firm in one’s home market may have been easy, but proved too difficult in different regions due to different market conditions, supply chains, cultural phenomena, and more.

Over time, this led the U-shaped firm to spontaneously innovate and decentralize into the multidivisional M-shaped structure. This saw corporations entrusting decision-making into lower-level divisions that oversaw different products or geographical areas of the business.

The influence of the M-shaped firm innovation is all around us. Today’s corporations hire dedicated product, marketing, and sales teams out of every geography it operates in, as opposed to concentrating them in headquarters.

M-shaped firms decentralized decision-making

Why the need to decentralize the firm? Building on Coase’s insight, later economists argued that there were two key driving forces of this structural decentralization into the M-shaped firm. The first sought to solve the constrained knowledge problems of planning that top managerial executives faced.

Large corporations face severe knowledge complications to effectively compete in a foreign market where the competitive conditions, supply chains, laws, and consumer sociocultural preferences were vastly different. The M-shaped firm allowed day-to-day decision-making to be made efficiently by divisional managers who better understood local circumstances, leaving upper management to focus on strategy.

The dominant success of General Motors (GM) in the 20th century was largely due to this organizational model of divisional independence that permitted mid to lower-level managers full operational autonomy. Amidst the crisis of 1920-1921 where GM experienced sales declines of 75% and record low productions, its long-time president Alfred Sloan pursued a radical decentralization of the organizational structure. Sloan emphatically stressed that divisional managers needed to be strictly “independent and may accept or reject the advice of [upper management] Advisory”. As he wrote in his blueprint:

“The General Manager formulates all the policies of his particular unit subject only to the executive control of the President. The responsibility of the head of each unit is absolute and he is looked upon to exercise his full initiative and ability in developing his particular operation to the fullest possible extent and to assume the full responsibility of success or failure.”

Just as socialist central planners failed abysmally to plan entire national economies because the knowledge required to do so could never be centralized in the hands of one government committee, large corporations faced similar problems as they expanded. Sloan’s M-shaped innovation proved successful for GM. The company surpassed its main competitor Ford and set the standard blueprint for all future capitalist corporations for the century to come.

Incentivizing work

The second driving factor toward the M-shaped firm revolved around incentive problems. Employees within the U-shaped firm had little incentive to work harder or be entrepreneurial in their job scopes when remuneration was tied to a salaried paycheck. From an accounting perspective, the firm sat on unused human capital assets. Profits were left on the sidewalk.

The innovation of the M-shaped firm improved the alignment of incentives and rewards to lower management, thereby allowing firms to leverage this dispersed knowledge throughout the organization. It enabled them to exercise their judgment and act as local “entrepreneurs” within the firm, to develop new subproduct variations, administrative processes, and tweak existing methods of production that better fit the economic conditions of that particular market.

Of course, top-level executives did not take a completely hands-off approach; some rules were still dictated from above. But the key point was that the M-shaped structure permitted some scope of decentralized adjustment and adaptation which was not possible in the U-shaped firm.

Enter DAOs

Readers familiar with DAOs can perhaps already see where this is going. Enabled by blockchains, DAOs are the next iteration in the continued decentralization of the modern capitalist firm.

M-shaped firms, like their U-shaped predecessor, are set to be disrupted by DAOs. The internet and smartphones have already started this ball rolling to some extent. Companies in the so-called gig economy like Uber, Airbnb, and TaskRabbit connect buyers and sellers in a somewhat decentralized fashion without being saddled with rigid hierarchical structures and long-term contracts.

What sets DAOs apart from all previous organizational forms is their flat, decentralized structures and absence of central planning. DAOs share a treasury and raise equity capital through the issuance of their own token, attracting anonymous investors and workers who believe in its mission.

The transparent nature of the blockchain means that all organization’s activities are managed on-chain and anyone can audit its smart contract codes, giving both investors and workers greater transparency into the inner workings of the organization.

In a traditional corporation where ownership was centralized, key strategic decisions regarding hiring or expansion were made exclusively by upper management behind closed doors. The M-shaped firm helped to mitigate part of that problem, but it was still a fundamentally centralized structure.

The decentralized ownership of DAOs lets anyone holding its native token exercise an active vote by connecting their wallet (with the tokens in it as verification) to a DAO voting platform such as Snapshot.

DAO-skeptics argue that not all members participate actively due to voter fatigue. There is a grain of truth here, but it greatly misses the relative improvements that DAOs bring to the table.

Even if not all members vote, the fact that organizational decisions can be publicly accessible and scrutinized by more active members is a dramatic improvement from traditional corporations where decisions are shrouded in secrecy.

An apt parallel we can draw here is the shift towards political monarchies to liberal democracies in the 20th to 21st century. Peer-reviewed research in political science finds that most voters today are politically apathetic, but political democracy at the very least allows an active minority of activists, journalists, and concerned citizens to dissent and raise awareness on selected issues.

Is that less ideal than full voter participation? Yes. But is it a significant improvement from authoritarian monarchies? A thousand times, yes.

Solving incentive problems

The economic marvel of DAOs lies in how it so superbly aligns the incentives between work and reward. Recall that the M-shaped firm emerged as a way for corporations to expand aggressively while reducing the need for top management to supervise.

This management philosophy was pioneered by Arthur Rock, the famed venture capitalist known for investing early in tech companies like Fairchild, Intel, and Apple Computers. Borrowing from his experiences with Fairchild Semiconductor in the 1950s, Rock pioneered the private limited partnership model that compensated upper management and junior employees with stock options, later becoming synonymous with Silicon Valley’s equity culture.

This was a radical departure from the times when equity was owned only by founders and venture capitalists.

Rock understood that incentives mattered and that for firms to succeed, key workers needed to be motivated beyond a salaried paycheck. With Fairchild, Rock ensured that key scientists and engineers who were integral to the success of the firm received stock options. This model of “liberation capital” introduced high-powered incentives for workers and unlocked human talent.

DAOs extend this economic logic to every worker. Like gig economy workers, most DAOs offer a flexible “pay for work” model. Unlike gig economy workers, however, DAO workers are paid in native tokens (equity). DAOs, therefore, empower workers with the best of both worlds: flexibility and stakeholdership. This gives them an even further vested interest in seeing the DAO organization grow.

Where are DAOs headed?

Common critiques of DAOs focus on the fact that not all forms of organizations will require a hyper-decentralized structure. This is true for a DAO with a singular mission and where reaching economies of scale are straightforward.

But this is less a criticism of DAOs per se, and more a matter of product market fit. Despite the massive innovation of the M-shaped firm, companies in industries such as metals, tobacco, and sugar did not immediately adopt it as the expansion was not bogged down by the same types of coordination problems.

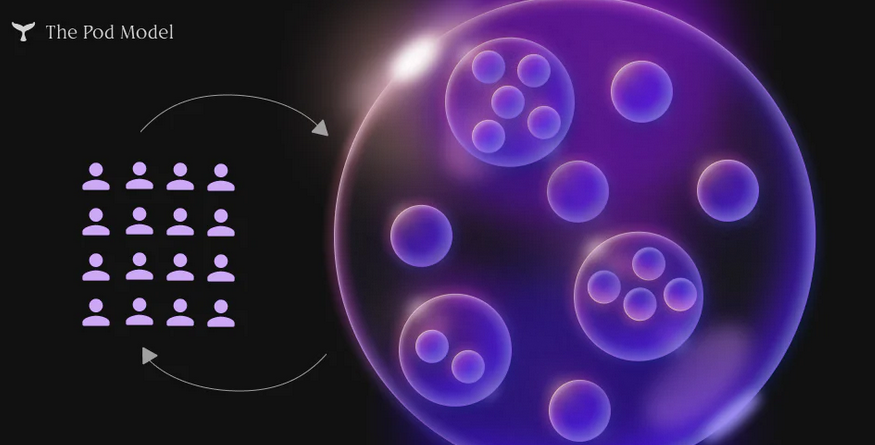

Another common critique points to the low participation barriers of DAOs that may bring about scalability issues. In a large DAO where decisions need to be made across different specialty areas, not everybody will have the knowledge or incentive to make the right call.

In response, DAO tools such as Orca Protocol or Aragon have surfaced to solve these problems. Orca facilitates the creation of “working groups” or mini-centralized departments (subDAOs) within the DAO that can spin up their own decision-making processes. Token holders would vote for representatives in these departments – a parallel to political democracy. This allows the DAO to scale decision-making efficiently in a way that maintains some form of decentralization.

A prominent example of this at play can be seen in the 25.5K members-strong GitconDAO. To scale decentralized decision-making, Gitcoin employs a community representative (known as stewards) system which members vote for to make decisions on their behalf. Steward’s duties cover anything from defining organizational processes, community building, fundraising, anti-fraud governance, and product strategy.

DAOs are still in their nascent stage, but the technological innovation of blockchains upon which it sits promises to solve coordination problems on an unprecedented scale.

Action steps

🗺️ Explore our previous think pieces around DAOs:

🧑🎓 Learn How to Join a DAO and How to Get Paid by DAOs

📖 Read Donovan’s previous article on Why Gamers Shouldn't Hate NFTs

Ryan Sean Adams

Ryan Sean Adams